75 billion in short-term liquidity to the repo market for the first time in nearly 11 years. When the dollar was added to the price, the reports overflowed, which saw this as a critical crisis signal.

Today I would like to solve for you the mystery behind this event. For this, of course, I have to delve deeper into the somewhat dry subject matter. But for long-term investors in particular, even "off-the-wall" background information can sometimes be extremely useful – if only to avoid getting caught up in market turmoil and the media barrage that often follows.

Short review of the expiration date

Before that, however, a short review of the expiration day: Contrary to my expectations in the previous week, the DAX nevertheless started its way upwards and thus forced the writers to hedge the large call positions at 12.500 and 12.600 points.

But the very big upward dynamic, which would have been possible with this expiration constellation, failed to materialize. On Thursday, the DAX with a "death doji" already started to retreat and closed at the expiration date on Friday with 12.669.84 points just above the largest call position of the October expiration.

So it could be that the breakout to a new high for the year was just an expiration day effect and the price will fall back again. The decision on this, as is often the case, is likely to depend on the U.S. indices, which in turn will be driven primarily by the results of the quarterly reporting season in the near term. In addition, investors will of course also be looking at the figures of the DAX companies, but these will only trickle in gradually over the coming weeks. This could cause the DAX to run sideways for a while longer.

The repo market – the unknown entity

And so to my topic today, the recent "turmoil" in the US repo market. These were already a good month ago. At that time, there was an unusual increase in the short-term interest rates that banks charge each other for so-called overnight transactions.

These rates should normally be just above the level of the Fed's policy rate band (currently: 1.75-2.00%), but below the so-called "discount window," which is the interest rate spread that the Fed charges banks for short-term liquidity loans. And that interest rate spread was 2.75% to 3.25% at the time (and was lowered to 2.5% to 3.0% at the September Fed meeting).

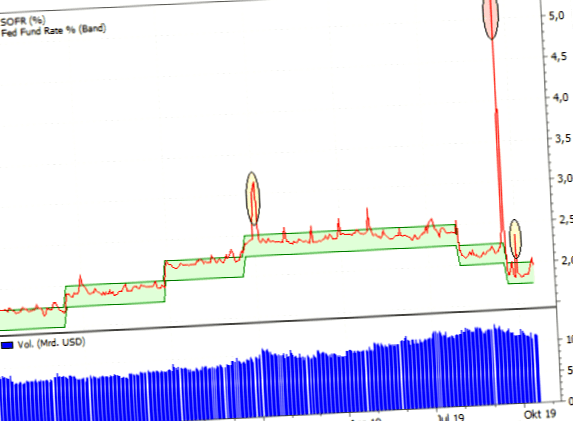

On Monday, 16. However, in September, interest rates jumped up to more than 6%. (Depending on the source and data provider, there has also been talk of short-term spikes of 8.5% or even 10%.) The official benchmark of this "overnight interest rate", the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) was still 5.25% on a daily basis (see red ellipse in the following chart).

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Media uproar over the "secrets" of the repo market

In the financial media, this increase caused some uproar, after all, the Fed then provided the repo market with significant short-term liquidity for the first time in almost 11 years, amounting to no less than. dollars available, of which 53 billion. Dollars were drawn down. Since then, the Fed has been acting almost daily on the repo market (see next chart, below). Some critics see this as a symptom of crisis ("The money market is drying up!") or fear a new QE program "through the back door". Both of these are wrong – I will explain the reasons below.

But first, the "secrets" of this ominous repo market, which is a closed book for almost all investors (and also for most analysts), because it is in fact only of interest to banks and a few other large investors.

Even the name is typical banker slang, because the exact designation is Repurchase Market, which means "buy-back market. The abbreviation "repo" is therefore merely an onomatopoeic shortening of the English word "repurchase". The fact that this market exists at all – in a similar way in all modern economies, by the way – is due to the prevailing monetary system. According to them, banks are obliged to hold a certain amount of money for every dollar, euro, yen, etc., that they lend., they lend or trade. This is the so-called minimum reserve requirement set by the central bank – in the U.S., the Fed. Assume that the minimum reserve is 10%. Then, for every $10 they receive in deposits from their customers, banks must hold $1 as a minimum reserve, and they can keep the remaining $9 z.B. lend as loans.

When money runs out

Occasionally, however, the cash holdings of a bank slip below this minimum. This is not unusual and in most cases is not a sign of an impending crisis! There can be z.B. it could simply be that customers are withdrawing more money than the bank anticipated. After all, banks process millions of transactions every day. Since no one can determine in advance exactly how much money will be left in the cash balance at the end of the day.

But even this is not a problem, since the entire banking system is interconnected and operates according to the same rules. And when a customer (z.B. a company) makes a transfer to z.B. to pay a bill and thus deprives his bank of liquidity, this amount usually flows to another bank (z.B. of the supplier), which consequently has a liquidity surplus.

Thus, a bank A that temporarily falls short of the minimum reserve must make up this difference at the close of business to meet the legal requirements. The bank then has to get "cash" for a very short period of time (usually overnight, because the following day's transactions shuffle the cards all over again). There are several ways to do this.

Nothing works without collateral, even in the repo market

Thus, Bank A z.B. simply take out a loan from the central bank at the discount rate. But that would be a simple money exchange transaction, because bank A parks the money again as a minimum reserve at the central bank. Besides, such transactions are frowned upon, because the banks should please solve such small, everyday problems among themselves. After all, a boss does not want his people to bother him about every little thing! Discount loans are therefore only taken out by banks in emergency situations.

So Bank A will take out a short-term loan from another Bank B (which has surplus cash reserves). But Bank B won't do that without collateral, since such loans can quickly run into hundreds of millions – which no bank is going to hand over just like that, not even "just" overnight.

As a rule, short-term government bonds are used as collateral; in the U.S., these are the so-called Treasury Bills (T-Bills) with maturities of a few days to one year. For this loan, Bank B receives a (very low) interest rate from Bank A, which is based on the prime rate on the one hand, and on the supply and demand for money or cash on the other hand. Collateral directed.

A normal credit contract? Not quite..

In principle, then, Bank A and B enter into a perfectly normal loan agreement. But such contracts are now highly standardized and automated. The peculiarity of this loan agreement is that when Bank A repays its loan to Bank B, it not only repays its debt but also gets its bonds back. (Bank B, in other words, is not allowed to otherwise dispose of the bonds it received as collateral from Bank A, but must hold them in safekeeping.) This is the buyback that gave this market its name.

Now, there can be bottlenecks in the repo market for a number of reasons. For one thing, there may simply be too little liquidity because the banks want to hold on to their money at all costs – as was the case at times during the financial crisis. Second, there may be shortages of collateral because there may be no suitably creditworthy bonds in circulation due to central bank purchases or too little government issuance activity. In extreme cases, the government's credit rating could also be so bad that banks would simply stop accepting the bonds.

Why the repo market recently got stuck

But all these reasons did not play a role in September in the USA. Instead, the following factors were blamed for the liquidity squeeze:

For one thing, companies drew down a lot of money to pay their quarterly corporate taxes due. (This factor regularly leads to "spikes" in the overnight yield curve at the end of the quarter, as shown in the chart above; see also yellow ellipses.). Second, $78 billion worth of U.S. Treasury bonds came onto the market at that time, which suddenly deprived banks and other large investors who routinely buy these bonds of liquidity.

On top of that, reserves parked by banks at the Fed were lower than at any time since 2011: they were $1.47 trillion, but that was just ca. 50 percent less than the 2014 peak. Despite this impressive sum, according to market experts, this meant that the (liquid) excess reserves that normally flow into the repo market were scarce. And a national holiday in Japan also caused an important external source of liquidity to dry up in the short term – after all, the yen is traditionally the most important carry currency in the money market.

If even the Fed is taken by surprise

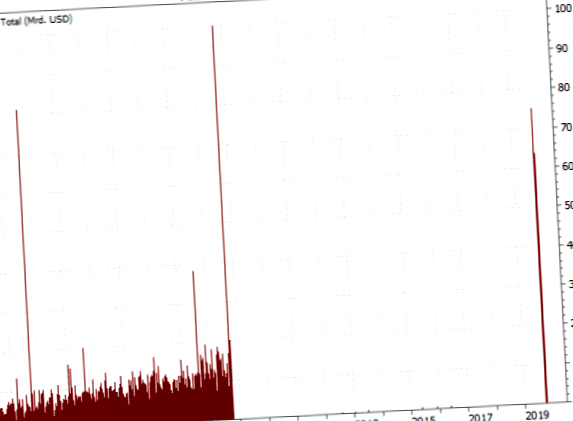

Last but not least, the Fed was caught on the wrong foot, because it too is – actually – an important player in the money market. However, as already mentioned above, the Fed has not had to act seriously in the repo market for almost 11 years. This non-action is what is actually unusual (and not the resumption of their participation) – because as the following chart shows, Fed intervention was commonplace before:

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

The 2008 break in this history was caused by the central bank, government and investors initially providing financial assistance and thus liquidity to banks very directly. As is well known, the Fed's low interest rates and later, of course, its bond-buying programs (QE programs; QE: quantitative easing) also created a glut of money in the financial sector. This chart shows that very impressively!

After almost 11 years of quasi-abstinence in the repo market (between 2012 and 2017, there were exactly 10 Fed "interventions" of minimal amounts, barely visible in the chart), the Fed was also avowedly somewhat surprised at the ferocity of the money squeeze. In addition, the Fed was probably very busy with its then imminent meeting.

How to evaluate current activity

It may be argued that the amounts that have recently been reintroduced seem comparatively high. Previously, similarly high amounts had to be repurchased only after the 11. September 2001 and expended in the 2008 financial crisis. But because of the extraordinarily large break in the data series, it is difficult to assess how the trend would have continued – possibly exponentially? Finally, the QE programs have also injected an extraordinary amount of liquidity into the system. So perhaps the current values have long been normal?

Alternatively, banks currently prefer to tap the Fed – for whatever reason. Possibly, therefore, values will go down again in the coming weeks and months. At any rate, no concrete conclusions or even fears of a crisis can be drawn from this – especially since the volumes of repo market transactions since September have not shown any abnormalities either (see blue columns in the lower part of the first chart).

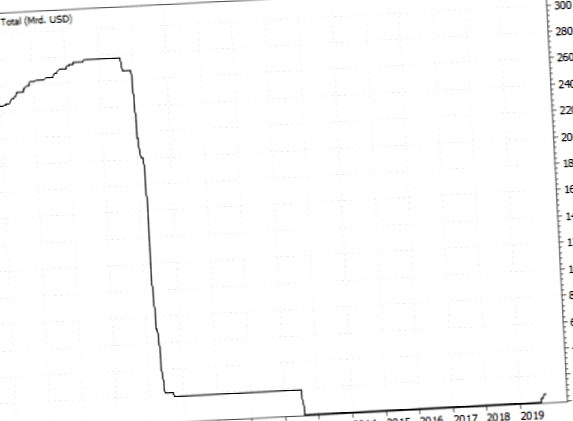

And the development of the holdings of collateral that banks deposit with the Fed for liquidity does not send any crisis signals either:

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

By 2008, the Fed's holdings of T-bills had climbed to a whopping 277 billion euros. Dollar. When the Fed ceased repo market activities, they fell very quickly; as of August 2012, they were even zero! Since September, they have increased to a very modest 6 billion. Dollar. A "run" on central bank money can therefore not be read out in any way.

Are repo transactions a covert QE program?

Of course, these activities of the Fed in the repo market increase the Fed's balance sheet – just as the bond purchase (QE) programs have done. And some analysts therefore believe that the "new" repo transactions (which are not so new, as we have seen) are a QE program through the back door.

But there is a key difference between repo activity and QE. T-bills purchased under repo transactions are short-term bonds with a maximum maturity of one year. So at most, the Fed is influencing short-term interest rates. But it does so anyway via the policy rate!

Under QE, on the other hand, the Fed bought long-term bonds and mortgage-backed securities to lower long-term interest rates (and boost credit demand). So the Fed's purchase of T-bills through repurchase agreements just keeps short-term interest rates closer to the Fed's targeted range. Long-term interest rates (ideally determined only by inflation expectations) remain unaffected! So repo transactions are a perfectly normal, perfectly everyday monetary policy that was not worth talking about in the past.

What is much more decisive for the markets now

But as already mentioned, the Fed's re-entry into the repo market is still too recent to conclusively clarify all questions at this point in time. So you can continue to keep an eye on the development of this part of the financial markets. But there is no reason at all to worry or even panic, contrary to media comments to the contrary.

At the moment, the chart condition of the stock markets is more decisive: If the DAX manages to break out to new highs for the year and the U.S. indices also break out above their (all-time) highs and neuralgic marks, the subsequent year-end rally should continue to drive prices up for quite some time – repo market or not. And 2020 is an election year in the USA. Election years, however, are traditionally known to be among the strongest years in the stock market. Then the recent events in the repo market will be forgotten very quickly.